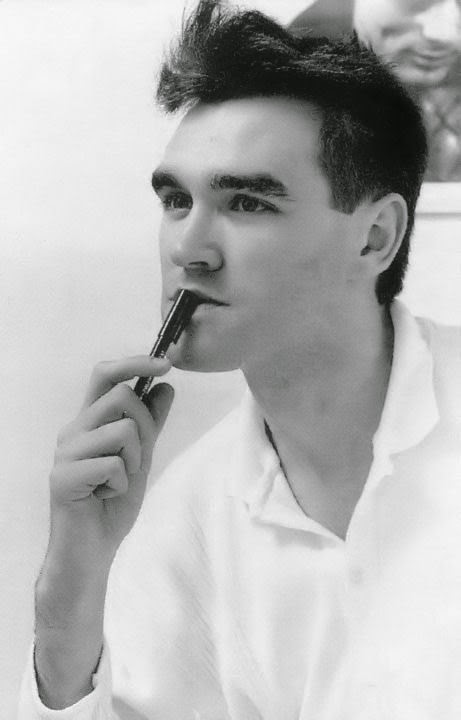

For all its strengths and weaknesses, the biggest surprise about Morrissey's Autobiography is that, when he turns his hand to prose, the author of some of the most memorable and soaring lyrics of our time flounders on the deck like Baudelaire's albatross, the giant wings of his literary pretensions impeding his progress at every turn. From the first four-and-a-half page paragraph, with its attempt at indentless stream-of-consciousness retrospect, you immediately wonder where, out of all the myriad books Morrissey has always talked of drowning in, he ever derived his sense of prose style from. If "le style est l'homme", his writing appears to suffer the same condition of being irredeemably arrested at some point in a troubled, self-absorbed yet desperate-to-impress adolescence as the book demonstrates his character to have always been.

It seems to me that Morrissey's earliest yet most abiding models are less Oscar Wilde or Dorothy Parker than the gonzoish poetasters of 70s music journalism - Charles Shaar Murray, Nick Kent and even the Julie Burchill he later meets and hissily satirises - those purveyors of streetwise counter-cultural diatribes and flighty paeans to the likes of Patti Smith hammered-out for the NME in an English where cynical, resonant chutzpah and gauche wordplay invariably wins out over syntactic cohesion or actually telling you anything insightful about the artist. The later post-punk generation of Ian Penman, Paul Morley, Dave McCullough et al - some of whom championed The Smiths during the 80s - were perhaps too much his contemporaries (and potential rivals, since journalism was one of Morrissey's youthful career-aspirations) to have impacted much on his style. Their reviews, although at least more considered and well-referenced, often had the opposite failing of becoming clogged up in their own attempted cleverness and weltering under the weight of half-baked, ill-digested critical theory: epitomes of that malady of pseudo-intellectualism which would culminate in Factory Record's hubristic implosion a few years later.

One definition of bad style in prose might be writing whose rhetoric and figurations obscure rather than aid the narrative progression of the text. To return to Autobiography's opening, the adoption of a hackneyed, faux-literary journalese is all too apparent, where no opportunity to make a facile rhyme- or homonym-parallel can be missed (as in the clunking zeugma "Streets to define you and streets to confine you, with no sign of motorway, freeway or highway"), where for the sake of dramatic effect sentences wobble out of grammatical sense like old Coronation Street sets("we walk in the center of the road, looking up at the torn wallpapers of browny blacks and purples as the mournful remains of derelict shoulder-to-shoulder houses, their safety now replaced by trepidation") and where the imagery (to chance my arm at a Morisseyan epiphet) is laid on with a hefty trowel the size of Hemel Hempstead. His depiction of the Manchester of his childhood makes Dickens on Victorian London seem as subtle and nuanced as Elizabeth Bowen: although some reviewers cited these passages as the best part of the book, they seem to me by far the worst, coagulating every dreary, belittling cliché about Northern grimness (cf. Monty Python's Four Yorkshiremen Sketch: "When I were a lad...") with that catastrophising of mawkish self-pity into full-blown persecution-complex which is so endemically Morrissey.

Once we are done with childhood and the laborious horror-show of his school -days (dealt with so much more succinctly and effectively 30 years ago in the Smiths' song 'The Headmaster Ritual') the book becomes steadily more readable and engaging, the prose relaxing into a less self-conscious, event-driven momentum, often leavened with acerbic wit and a sense of the absurd. It's an undoubted shame that the story of The Smiths - surely the aspect of Morrissey's life most of us would go to these pages to learn more of - is rushed through so cursorily, as though such momentous artistic achievements have apparently now been overshadowed by the subsequent, lengthily-dissected trial in which he feels himself (with some justice) betrayed by his former band-members.

Far more space is given to the solo-career and in fact by the ending we realise that for all its subject's eccentricity the book follows pretty much the rags-to-riches trajectory of all celebrity-biogs, although unlike most contemporary also-rans who are famous for being very fleetingly televised, you do feel that Morrissey - with the blind self-belief and persistent integrity of the true artist - may genuinely have earned his late-in-the-day acclaim. Scores have been settled (with Geoff Travis, Tony Wilson, Judge John Weeks etc.), a kind of laconic wisdom has been wrung from decades of worldwide fan-adulation ("I am no more unhappy than anyone else") but whether Morrissey has finally learned to move on from those lamentable memories of his youth - or the lamentable prose he enshrines them in - remains somewhat unlikely.

Far more space is given to the solo-career and in fact by the ending we realise that for all its subject's eccentricity the book follows pretty much the rags-to-riches trajectory of all celebrity-biogs, although unlike most contemporary also-rans who are famous for being very fleetingly televised, you do feel that Morrissey - with the blind self-belief and persistent integrity of the true artist - may genuinely have earned his late-in-the-day acclaim. Scores have been settled (with Geoff Travis, Tony Wilson, Judge John Weeks etc.), a kind of laconic wisdom has been wrung from decades of worldwide fan-adulation ("I am no more unhappy than anyone else") but whether Morrissey has finally learned to move on from those lamentable memories of his youth - or the lamentable prose he enshrines them in - remains somewhat unlikely.

No comments:

Post a Comment