It's not only our bodies that undergo a glut of inertia and unhealthy torpor during Christmas; our mental faculties can also face a kind of catatonic shutdown under the weight of endless repeats and festive specials on TV, Roy Wood, Noddy Holder and all the other anthems churned out on a mind-numbing loop, the logorrhoeic reiteration of banal cliches and marketing slogans thinly disguised as messages of Christian goodwill. Geoffrey Hill might now resemble a grouchy Santa Claus, but what was that old line of his about "wild Christmas": "What is that but the soul's winter sleep?" I also like this obstreperous chunk of early Christopher Middleton:

" Shit

On

You,

Mother.

All I wanted was out:

To be free

From your festoons

Of plastic

Everlasting

Christmas cards." ('The Hero, On Culture')

I had fun, sure, and it was great to spend time with my son and wider family. But also good to get the brain back in gear with some challenging reading whose intellectual rigor seems to counteract the prevailing mood of self-indulgent sloth. Robert Sheppard on Middleton, for example, in The Wolf 31 is a superb delineation of this poet's unique and far-reaching approach towards poetic form, with particular reference to the essay 'Reflections on a Viking Prow'. Sheppard's enthusiasm and willingness to draw significant principles from Middleton's theories echoes my own post on the essay from last December, No Longer A Mere Blob.

Andrew Duncan's piece about his critical explorations of contemporary British poetry - 'Lost Time is not Found Again' - communicates an insistence parallel on the need for an impersonal poetic, a seeing beyond the glib appraisal of a period by merely looking at its few most acclaimed poets. Similarly, Jerome Rothenberg is a figure whose tenacious endeavour over many years has been (in seminal anthologies like Technicians of the Sacred) to bring to light poetic voices well outside the literary mainstream and its predilection for male, white, university-educated liberal-humanists: the interview with Rothenberg in this edition of The Wolf demonstrates how active and tireless this under-appreciated project remains.

The magazine also contains my review of Hill's Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952-2012, by far the most difficult text of this kind I've had to write. As a point of comparison there's an excellent, illuminating review of the same book by Karl O'Hanlon in the new Blackbox Manifold, where you can also find interesting poems by Helen Tookey, Allen Fisher and Karthika Nair.

Also worth a prolonged look is the online journal Prac Crit edited by Sarah Howe - its title presumably a nod to IA Richards, not a bad figure to revaluate. I particularly enjoyed the interview with Tim Donnelly conducted by Dai George and Olli Hazzard's intricate, beguiling interpretation of 'Last Dream of Light Released from Sea-Ports' from The Cloud Corporation.

ictus [ik-tuhs] 1. In prosody the stress, beat or rythmical accent of a poem 2. In medicine a seizure, a stroke or the beat of the pulse

ictus

Tuesday, 30 December 2014

Monday, 22 December 2014

Sunday, 30 November 2014

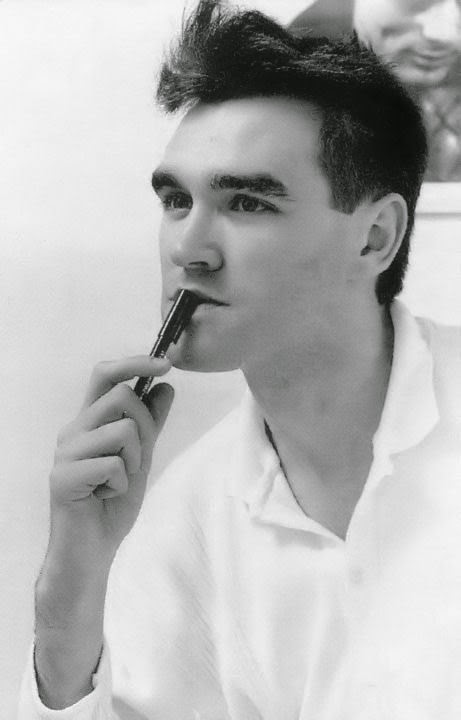

The Syntax of Memory: Morrissey's Autobiography

For all its strengths and weaknesses, the biggest surprise about Morrissey's Autobiography is that, when he turns his hand to prose, the author of some of the most memorable and soaring lyrics of our time flounders on the deck like Baudelaire's albatross, the giant wings of his literary pretensions impeding his progress at every turn. From the first four-and-a-half page paragraph, with its attempt at indentless stream-of-consciousness retrospect, you immediately wonder where, out of all the myriad books Morrissey has always talked of drowning in, he ever derived his sense of prose style from. If "le style est l'homme", his writing appears to suffer the same condition of being irredeemably arrested at some point in a troubled, self-absorbed yet desperate-to-impress adolescence as the book demonstrates his character to have always been.

It seems to me that Morrissey's earliest yet most abiding models are less Oscar Wilde or Dorothy Parker than the gonzoish poetasters of 70s music journalism - Charles Shaar Murray, Nick Kent and even the Julie Burchill he later meets and hissily satirises - those purveyors of streetwise counter-cultural diatribes and flighty paeans to the likes of Patti Smith hammered-out for the NME in an English where cynical, resonant chutzpah and gauche wordplay invariably wins out over syntactic cohesion or actually telling you anything insightful about the artist. The later post-punk generation of Ian Penman, Paul Morley, Dave McCullough et al - some of whom championed The Smiths during the 80s - were perhaps too much his contemporaries (and potential rivals, since journalism was one of Morrissey's youthful career-aspirations) to have impacted much on his style. Their reviews, although at least more considered and well-referenced, often had the opposite failing of becoming clogged up in their own attempted cleverness and weltering under the weight of half-baked, ill-digested critical theory: epitomes of that malady of pseudo-intellectualism which would culminate in Factory Record's hubristic implosion a few years later.

One definition of bad style in prose might be writing whose rhetoric and figurations obscure rather than aid the narrative progression of the text. To return to Autobiography's opening, the adoption of a hackneyed, faux-literary journalese is all too apparent, where no opportunity to make a facile rhyme- or homonym-parallel can be missed (as in the clunking zeugma "Streets to define you and streets to confine you, with no sign of motorway, freeway or highway"), where for the sake of dramatic effect sentences wobble out of grammatical sense like old Coronation Street sets("we walk in the center of the road, looking up at the torn wallpapers of browny blacks and purples as the mournful remains of derelict shoulder-to-shoulder houses, their safety now replaced by trepidation") and where the imagery (to chance my arm at a Morisseyan epiphet) is laid on with a hefty trowel the size of Hemel Hempstead. His depiction of the Manchester of his childhood makes Dickens on Victorian London seem as subtle and nuanced as Elizabeth Bowen: although some reviewers cited these passages as the best part of the book, they seem to me by far the worst, coagulating every dreary, belittling cliché about Northern grimness (cf. Monty Python's Four Yorkshiremen Sketch: "When I were a lad...") with that catastrophising of mawkish self-pity into full-blown persecution-complex which is so endemically Morrissey.

Once we are done with childhood and the laborious horror-show of his school -days (dealt with so much more succinctly and effectively 30 years ago in the Smiths' song 'The Headmaster Ritual') the book becomes steadily more readable and engaging, the prose relaxing into a less self-conscious, event-driven momentum, often leavened with acerbic wit and a sense of the absurd. It's an undoubted shame that the story of The Smiths - surely the aspect of Morrissey's life most of us would go to these pages to learn more of - is rushed through so cursorily, as though such momentous artistic achievements have apparently now been overshadowed by the subsequent, lengthily-dissected trial in which he feels himself (with some justice) betrayed by his former band-members.

Far more space is given to the solo-career and in fact by the ending we realise that for all its subject's eccentricity the book follows pretty much the rags-to-riches trajectory of all celebrity-biogs, although unlike most contemporary also-rans who are famous for being very fleetingly televised, you do feel that Morrissey - with the blind self-belief and persistent integrity of the true artist - may genuinely have earned his late-in-the-day acclaim. Scores have been settled (with Geoff Travis, Tony Wilson, Judge John Weeks etc.), a kind of laconic wisdom has been wrung from decades of worldwide fan-adulation ("I am no more unhappy than anyone else") but whether Morrissey has finally learned to move on from those lamentable memories of his youth - or the lamentable prose he enshrines them in - remains somewhat unlikely.

Far more space is given to the solo-career and in fact by the ending we realise that for all its subject's eccentricity the book follows pretty much the rags-to-riches trajectory of all celebrity-biogs, although unlike most contemporary also-rans who are famous for being very fleetingly televised, you do feel that Morrissey - with the blind self-belief and persistent integrity of the true artist - may genuinely have earned his late-in-the-day acclaim. Scores have been settled (with Geoff Travis, Tony Wilson, Judge John Weeks etc.), a kind of laconic wisdom has been wrung from decades of worldwide fan-adulation ("I am no more unhappy than anyone else") but whether Morrissey has finally learned to move on from those lamentable memories of his youth - or the lamentable prose he enshrines them in - remains somewhat unlikely.

Monday, 10 November 2014

Autumn in Grasmere

|

| Dove Cottage from its garden |

Had an idyllic few days in the Lake District over the half-term, my first excursion to the region. I could wax Wordsworthian about the extraordinary autumnal landscapes I walked through until the rare-breed cows come home but of course you've heard it all before. What I found amazing was how the mountains, lakes and woods in fact lived up to the centuries-old hype and despite a highly-developed tourist-trade in the area, seem to remain irreducible to chocolate-box prettification or the "aw-shucks vision of immensities" William Logan mocked Charles Wright for. (Strange how we use "unspoilt" as a term of approval as though all natural environments were ultimately destined for spoliation.)

|

| View from Hawth Castle |

The landscapes and bewilderingly wide skies, across which patterns of cloud-filtered light continually roam and shift, retain something inhospitably wild and barren about them which is the opposite of the "cramped and fearful" box-life of the indentured Londoner.(The quote's from MacDiarmid's great poem 'Bagpipe Music', quite germane to what I'm talking about). No wonder in the late 18th century certain ladies would be advised to observe the Lakes with the aid of a Claude glass - basically a mirror that would frame and render picturesque the otherwise unassimably natural abundance in front of them - lest the vertiginous wilderness would throw them into a swoon.

|

| Lake Windermere

|

Now many of us use our smartphones and tablets for a similar mediation, a similar inability to take on board the enormous unhumanness of these locations society has yet to monetise and co-opt. Places where the depressing corollary of post-modernism - "il n'y a pas d'hors-texte" - feels like it's unravelled and where the outside goes on forever.

Thursday, 23 October 2014

Dizzily Hereafter: Donnelly in Notting Hill

Last week I ran through rain to attend the Q&A and reading by Timothy Donnelly at the Lutyens and Rubinstein Bookshop in W11. The initial conversation with Adam Phillips was both illuminating and amusing for the way Phillips' earnestly soft-spoken, chin-stroking psychoanalytical manner often abutted against Donnelly's fast-talking and wryly down-to-earth Americanese, his speech-rhythms and frequent witty self-qualifications not a million miles from the peculiar syntactic propulsion of his poetry. In reading aloud he was careful to accentuate the acoustic richness of his lines, the "phrases of their idiosyncratic music"(to quote from a Stevens poem Donnelly said was particularly influential on him as a young man, 'Jasmine's Beautiful Thoughts Underneath The Willow'.)

If the poems of The Cloud Corporation seem to operate more often than not on a level of ambivalent abstraction, preoccupied with the blurred interface between perceiving mind and fluctuant reality, it was fascinating to hear Donnelly provide background-context for certain poems I was familiar with and dramatically reconfigure their meaning for me. The opening poem in the book, for example, - 'The New Intelligence' - came out of a period of debilitating illness when Donnelly was experiencing bouts of deafness in one ear and dizziness so extreme he would fall over. Doctors at the time could come to no diagnosis and the poet actually feared for his life: only after one specialist decided that Donnelly was suffering from a Sensory Processing Disorder - a lifelong condition he could learn to adjust to rather than a disease - that he could begin to recover his sense that a shared future with his wife and a faith in the objective world (rather than "the mind that fear and disenchantment fatten") was again possible. This then is what the poem addresses, although obviously at a querying slant: most startling for me was the realisation that the ending of the poem, which I'd taken to be hoveringly metaphorical, is pretty much literal and therefore incredibly poignant:

"I won't be dying after all, not now, but will go on living dizzily

hereafter in reality, half-deaf to reality, in the room

perfumed by the fire that our inextinguishable will begins"

If the poems of The Cloud Corporation seem to operate more often than not on a level of ambivalent abstraction, preoccupied with the blurred interface between perceiving mind and fluctuant reality, it was fascinating to hear Donnelly provide background-context for certain poems I was familiar with and dramatically reconfigure their meaning for me. The opening poem in the book, for example, - 'The New Intelligence' - came out of a period of debilitating illness when Donnelly was experiencing bouts of deafness in one ear and dizziness so extreme he would fall over. Doctors at the time could come to no diagnosis and the poet actually feared for his life: only after one specialist decided that Donnelly was suffering from a Sensory Processing Disorder - a lifelong condition he could learn to adjust to rather than a disease - that he could begin to recover his sense that a shared future with his wife and a faith in the objective world (rather than "the mind that fear and disenchantment fatten") was again possible. This then is what the poem addresses, although obviously at a querying slant: most startling for me was the realisation that the ending of the poem, which I'd taken to be hoveringly metaphorical, is pretty much literal and therefore incredibly poignant:

"I won't be dying after all, not now, but will go on living dizzily

hereafter in reality, half-deaf to reality, in the room

perfumed by the fire that our inextinguishable will begins"

Sunday, 19 October 2014

Blackout: A Poem from Human Form

Like

patient abrasion of a dug-out artefact

brittled

with age, to grasp what’s come to light,

you

chafe the jaded Swan Vesta across

its

worn sandpaper-page – in that dank

yellow

box the crumbly duds outweigh

the

live. We hunch around you in mumbling

suspense,

like Neanderthals at their first glimpse

of

fire. At last, a cursive scribble detonates

with

a sound like Velcro unseaming.

We

recoil a touch, as you stoop, and communicate

the

momentary, palm-cupped flame to a candle:

a

glow-worm sacrificed to a glow-animal.

That

abrupt blackout – moments before,

as

though the whole house fell unconscious -

had

you rooting through cupboards, rifling drawers

like

an intruder to unearth these instruments

of

sight, locating the children through a sonar

of

name-calls and blindman’s-buff gropings.

Soon

enough, the living-room’s ushered back

as

a woozy apparition coaxed from tea-lights,

eery for a moment as a séance

or

Hall of Rest. But someone’s prised out

a

November sparkler or two, crackling-bright

and

acrid: they arc-weld the candle-haloes together

and

sear a blurred initial on your retina.

Bereaved

of TV, we soon lope to bed, probing

with

torch-beam the wraith-mobbed corridor

of

the stairs. I colonise the freezing sheets

inch

by inch, resisting awhile the liminal dreams

that

muster in the frostscapes on our window,

afraid

to miss the sleep-balm of your last Goodnight;

then

burrowing deeper, mining for warm,

I

replay my body’s initial unclenching

in

the vivid, tactile blackness of your womb.

First published in Human Form, March 2013

Sunday, 12 October 2014

Tuesday, 23 September 2014

Charlotte Mew

Came across this by accident on an interesting website:

http://historyofmentalhealth.com/2014/03/23/1928-charlotte-mew/

Serendipitous too as I recently read of Charlotte Mew in Tim Kendall's excellent Oxford Book of First World War Poetry, which I wrote a review of over the summer. I recall an collection of her poems being brought out by Virago in the '80s - remember those alluring green editions?

Sunday, 14 September 2014

Old is the New New

The PBS Next Generation list of "the most exciting new poets" is extraordinary in that there is nothing new about it. Every poet selected either already has an established reputation or has been a prize-winner or had a debut that's been a PBS Choice. Is this promotion primarily about taking risks on encouraging and nurturing new poetry or is it rather on the whole a desperate bid in the face of a shrinking market to bolster the careers of poets with proven track-records of achievement, an exercise more akin to hedge-fund management than to the discovery of fresh, unheard styles and voices?

I say desperate because some of the choices are a little baffling. Adam Foulds is a fine writer but he has only published one book of poetry The Broken Word (impressive as it was) and that was back in 2008; since then he's produced two novels and as far as I know no poetry by him has appeared in magazines or journals. In other words, the impression is that Foulds is now concentrating his energies on prose and indeed is invariably described as a novelist . I can't see by what stretch of the imagination Foulds could be described as a new poet "currently lighting up the scene"; but he's a successful writer, he's won awards and prizes and I'm sure Cape (part of Random House) could do with selling a few more copies of The Broken Word.

Equally, Sam Willets brought out one book in 2010, New Light for the Old Dark, which has some good poems in it but has published nothing since. Like many people, I like Mark Waldron's work: his idiosyncratic friskiness with language can appeal to admirers of both the "post-avant" and the more mainstream (though these facile definitions have inter-curdled of late, in part because of poets like Waldron.) He's had two volumes out and is a well-respected figure on the scene, looked up to by younger poets, getting towards being something of an eminence grise: but "sparky" new poet?

It's positive that there are more women than men on the list, of course, with some genuinely worthy inclusions like Heather Phillipson and the performance poet Kate Tempest (also nominated for the Mercury Prize - now that's an exciting first). And positive that a poet published by an independent press like Penned in the Margins - Melissa Lee-Houghton - should be recognised, although this is very much the anomaly among a preponderance of Faber, Carcanet and Cape authors.

I'm aware that having an existing reputation within the poetry world doesn't mean that any of these writers couldn't do with their work being further talked about, promoted and marketed. It doesn't of course mean that you're making a steady income from poetry or have in any way "made it" as a writer. Given sufficient funding it would be beneficial if more than one initiative like this could be happening, with more backing awarded to promising poets who have yet to have their first book published; but something I learnt at the Penned in the Margins discussion panel last week (part of their ten year anniversary celebrations) is that more poetry-books are being published by a greater number of publishers than ever before but in fact less copies are being sold. That's quite a bleak conundrum, isn't it?

In that kind of scenario, with smaller presses and of course online printing gathering in importance, it's clear we need to be looking beyond PBS promotions to locate where the genuinely new and exciting currents in British poetry are coming through.

Check out the Next Generation 2014 here:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/sep/11/next-generation-20-poets-poetry-book-society-kate-tempest

I say desperate because some of the choices are a little baffling. Adam Foulds is a fine writer but he has only published one book of poetry The Broken Word (impressive as it was) and that was back in 2008; since then he's produced two novels and as far as I know no poetry by him has appeared in magazines or journals. In other words, the impression is that Foulds is now concentrating his energies on prose and indeed is invariably described as a novelist . I can't see by what stretch of the imagination Foulds could be described as a new poet "currently lighting up the scene"; but he's a successful writer, he's won awards and prizes and I'm sure Cape (part of Random House) could do with selling a few more copies of The Broken Word.

Equally, Sam Willets brought out one book in 2010, New Light for the Old Dark, which has some good poems in it but has published nothing since. Like many people, I like Mark Waldron's work: his idiosyncratic friskiness with language can appeal to admirers of both the "post-avant" and the more mainstream (though these facile definitions have inter-curdled of late, in part because of poets like Waldron.) He's had two volumes out and is a well-respected figure on the scene, looked up to by younger poets, getting towards being something of an eminence grise: but "sparky" new poet?

It's positive that there are more women than men on the list, of course, with some genuinely worthy inclusions like Heather Phillipson and the performance poet Kate Tempest (also nominated for the Mercury Prize - now that's an exciting first). And positive that a poet published by an independent press like Penned in the Margins - Melissa Lee-Houghton - should be recognised, although this is very much the anomaly among a preponderance of Faber, Carcanet and Cape authors.

I'm aware that having an existing reputation within the poetry world doesn't mean that any of these writers couldn't do with their work being further talked about, promoted and marketed. It doesn't of course mean that you're making a steady income from poetry or have in any way "made it" as a writer. Given sufficient funding it would be beneficial if more than one initiative like this could be happening, with more backing awarded to promising poets who have yet to have their first book published; but something I learnt at the Penned in the Margins discussion panel last week (part of their ten year anniversary celebrations) is that more poetry-books are being published by a greater number of publishers than ever before but in fact less copies are being sold. That's quite a bleak conundrum, isn't it?

In that kind of scenario, with smaller presses and of course online printing gathering in importance, it's clear we need to be looking beyond PBS promotions to locate where the genuinely new and exciting currents in British poetry are coming through.

Check out the Next Generation 2014 here:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/sep/11/next-generation-20-poets-poetry-book-society-kate-tempest

Saturday, 6 September 2014

Optic Nerve

Pubs and poets go together like the yin and yang of the known universe, inseparable and insoluble. In every pub in the UK there is a poet sitting in the corner scribbling gnomic fragments with prosodic marks over them, mouthing odd syllable-shapes, waiting to be bought another drink: they are part of the fixtures and fittings inherited from one landlord to the next along with the jukebox, the darts-board and the large dark stain on the carpet. The Dream-Songs would not be the randomised jibber-jabber conflating lyric profundity with maudlin prattle they are if Berryman had not composed many of them in bars and Dublin pubs: they boldly enact the woozy decline into incoherence, the loss of all sense of epistemological proportion and the sheer joy of talking bollocks that accompanies the pub-philosopher's nightly (or daily) downward spiral, immersed in this zone of permissible transgression like Hamlet's king of infinite space, deferring the bad dreams of next morning.

I say this by way of preamble to a new blog myself and some friends have embarked on, with a focus on writing about interesting or characterful pubs we come across both in London and outside it, posting reviews that will hopefully also be interesting and characterful. It's intended as a celebration of the pub in all its diversity in a time of widespread decline (31 pubs closing a week) when for God's sake we need it more than ever. What other manifestations of communal interaction do we have to offer in the UK that we haven't stolen from other cultures? Morris dancing? The greasy spoon café?

How else are you going to escape from the diurnal grind of quiet desperation that 'austerity Britain' has pushed you into? Sit at home reading poetry?

The blog's called The Optic - see what I've done there? - so please take a look at the opening chapter:

optic1.blogspot.co.uk

I say this by way of preamble to a new blog myself and some friends have embarked on, with a focus on writing about interesting or characterful pubs we come across both in London and outside it, posting reviews that will hopefully also be interesting and characterful. It's intended as a celebration of the pub in all its diversity in a time of widespread decline (31 pubs closing a week) when for God's sake we need it more than ever. What other manifestations of communal interaction do we have to offer in the UK that we haven't stolen from other cultures? Morris dancing? The greasy spoon café?

How else are you going to escape from the diurnal grind of quiet desperation that 'austerity Britain' has pushed you into? Sit at home reading poetry?

The blog's called The Optic - see what I've done there? - so please take a look at the opening chapter:

optic1.blogspot.co.uk

Thursday, 4 September 2014

Tuesday, 19 August 2014

In Their Own Words

If you missed it here's the first part of an interesting new BBC4 series comprised of old BBC footage of 20th Century poets edited together in chronological fashion to form a (very) basic history of British poetry. The opening clips of Pound show what an amazing place the castle in the Tyrol he came to live in towards the end of life was: he seems serene there, as against the impression the last fragmentary Cantos and Donald Hall's Paris Review interview (1960 I think) give of an old man "mired in depression". Great to see Hugh MacDiarmid speaking on film, especially in the context of the forthcoming Scottish referendum ("England must disappear") and equally RS Thomas talking in his flinty way about Wales and the way religion and poetry co-existed for him - were, in effect, one.

Auden on Parkinson is an amusing oddity, although Betjeman on the same programme is merely a low-brow showman (not shaman). And if I hear Dylan Thomas doing that ridiculous hammy singsong on 'Do Not Go Gentle' once more this year I'm going to scream:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b04dg1lz/great-poets-in-their-own-words-1-making-it-new-19081955

Afterword: the link to iPlayer is no longer live but you can catch the two parts of Great Poets In Their Own Words on YouTube. It's chopped into 15minute segments so I'm not going to provide links to all the parts.

Auden on Parkinson is an amusing oddity, although Betjeman on the same programme is merely a low-brow showman (not shaman). And if I hear Dylan Thomas doing that ridiculous hammy singsong on 'Do Not Go Gentle' once more this year I'm going to scream:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b04dg1lz/great-poets-in-their-own-words-1-making-it-new-19081955

Afterword: the link to iPlayer is no longer live but you can catch the two parts of Great Poets In Their Own Words on YouTube. It's chopped into 15minute segments so I'm not going to provide links to all the parts.

Monday, 18 August 2014

'Measuring the Dead': McCabe's In the Catacombs

Last summer I participated in the walk around West Norwood Cemetery which was the culmination of Chris McCabe's project reflecting on the resting-places and reputations of twelve poets buried there and examining whether any of them warranted being rescued from the oblivion of the unread. As well as being a fascinating exploration of the lives of obscure writers (contextualised with intriguing tangential information from local historian Colin Fenn), it was a beautiful sunny day and the walk around the leafy, placid cemetery stands out in my memory as among the vividest moments of that long summer. I tried to capture a sense of this in the pictorial record I posted afterwards, Ephemeral Stones.

Last summer I participated in the walk around West Norwood Cemetery which was the culmination of Chris McCabe's project reflecting on the resting-places and reputations of twelve poets buried there and examining whether any of them warranted being rescued from the oblivion of the unread. As well as being a fascinating exploration of the lives of obscure writers (contextualised with intriguing tangential information from local historian Colin Fenn), it was a beautiful sunny day and the walk around the leafy, placid cemetery stands out in my memory as among the vividest moments of that long summer. I tried to capture a sense of this in the pictorial record I posted afterwards, Ephemeral Stones.A year later Chris's prose-narrative about the project - In the Catacombs: A Summer among the Dead Poets of West Norwood Cemetery - has appeared and its a compelling read in a diverting, Iain Sinclair-like compound-form: part-autobiography, part-poetry criticism, part-literary and social history, part-Gothic fantasy/prose-poem. The delineation of his research into the obscure poets' lives and works is illuminated by pointed insights into figures like Hopkins, Dickinson and Rimbaud - whose masterpieces very nearly escaped the posthumous acclaim we now accord them - as well as the formerly-lionised Tennyson and Swinburne whose august lines seem to be embedded within the intricate Victoriana of the cemetery. In following McCabe's obsession with deceased poets and their place within history and society we come to realise that this is very much a personal journey in itself, an attempt to locate himself and his work within the shifting currents of poetic tradition as well as a struggle for reconciliation with a past represented by memories of his dead father.

It's encouraging to witness a comparatively young poet attempt to engage with the historically-grounded poetry of previous eras like this, disowning the unsatisfactory templates deployed by his contemporaries and disentangling the roots of his practice through a sensitive recognition of form and rhythm to gain a renewed sense of his own potential claim to literary posterity.

Thursday, 14 August 2014

Coffee With Joyce

As part of a camping trip to Istria in northern Croatia, I discovered this tribute to my favourite writer James Joyce at Cafe Uliks (Croatian for Ulysses) in the beautiful Italianate town of Pula. The bronze statue seems a substandard second-cousin of Gaudier-Brzeska's head of Ezra Pound - whether that's a deliberate reference given their connection I'm not sure.

Pula was the first place Joyce lived in after he had eloped from Dublin with Nora Barnacle in late 1904, then called Pola and part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He taught English here at the Berlitz School for some months before moving on to Trieste, the first city of the famous peripatetic trio of locations cited on the last page of Ulysses. It seems a suitably multicultural, polyglot meeting-place for a writer who incorporated so many languages into his prose: I recall there being Serbo-Croat and Hungarian words melded into Finnegans Wake from the time I studied it intensely although the references escape me now. The head of the Berlitz Schools in Pola and Trieste, the euphonious Almidano Artifoni, is immortalised in Ulysses by lending his name (somewhat improbably) to Stephen's music teacher, to whom he speaks Italian in the 'Wandering Rocks' chapter.

I also came across an allusion to Pula in Dante, Joyce's favourite writer:

"As at Arles where the Rhone sinks into stagnant marshes,

as at Pola by the Quarnaro Gulf, whose waters

close Italy and wash her farthest reaches,

the uneven tombs cover the even plain..."

Pula was the first place Joyce lived in after he had eloped from Dublin with Nora Barnacle in late 1904, then called Pola and part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He taught English here at the Berlitz School for some months before moving on to Trieste, the first city of the famous peripatetic trio of locations cited on the last page of Ulysses. It seems a suitably multicultural, polyglot meeting-place for a writer who incorporated so many languages into his prose: I recall there being Serbo-Croat and Hungarian words melded into Finnegans Wake from the time I studied it intensely although the references escape me now. The head of the Berlitz Schools in Pola and Trieste, the euphonious Almidano Artifoni, is immortalised in Ulysses by lending his name (somewhat improbably) to Stephen's music teacher, to whom he speaks Italian in the 'Wandering Rocks' chapter.

I also came across an allusion to Pula in Dante, Joyce's favourite writer:

"As at Arles where the Rhone sinks into stagnant marshes,

as at Pola by the Quarnaro Gulf, whose waters

close Italy and wash her farthest reaches,

the uneven tombs cover the even plain..."

Inferno, Canto IX, tr, John Ciardi

Basically Dante's drift is that Pola was the site of an extensive Roman cemetery (ie. a pagan sepulchre comparable to the one he finds in the City of Dis). Pula today still boasts some impressive Roman monuments such as the amphitheatre and Forum.

Basically Dante's drift is that Pola was the site of an extensive Roman cemetery (ie. a pagan sepulchre comparable to the one he finds in the City of Dis). Pula today still boasts some impressive Roman monuments such as the amphitheatre and Forum.

Friday, 18 July 2014

Holiday Reading

|

| Karthika Nair |

Among other things, I've been dipping into the new edition of The Wolf, whose wonderful opening poem by Karthika Nair is a potent blast of strange, estranging language; the nested, protean form of Sophie Mayer's prose-poem 'Silence,Singing', incorporating criticism, history and autobiography in a compelling assemblage, also stood out for me. There are thought-provoking reviews of Muriel Rukeyser's Selected and a collection of the envelope-poems of Emily Dickinson (this also by Sophie Mayer) - in both cases convincing me that these are books I need to acquire.

I also took receipt of Soapboxes, a new KFS pamphlet by Wolf editor James Byrne. In it he turns his hand to the somewhat disregarded genre of the political satire, excoriating with savage wit both the media-saturated, hyper-commodified banality of Little England and the bible-wielding, war-mongering American Far-Right personified by Sarah Palin. With Pound's scabrous Hell Cantos as a reference-point, Byrne elaborates a powerful invective in a time of wholesale political disaffection and apathy.

Byrne's clearly been writing intensively of late as he also has two full collections forthcoming later in the year, one from his UK publisher Arc (White Coins) and one from US imprint Tupelo Press (Everything That is Broken Up Dances). An intriguing sampler of work from these books can be read in the new Blackbox Manifold 12, alongside poetry by Zoe Skoulding and Kelvin Corcoran:

http://www.manifold.group.shef.ac.uk/

Thursday, 17 July 2014

Monday, 7 July 2014

The Fascination of What's Difficult

One of the upshots of the recent, tiresome Forward-orchestrated Paxman mini-controversy was the news that UK poetry book-sales have fallen (as have - to put it in context somewhat - all UK book-sales) from not very many at all to even less. One recalls Todd Swift's bleak estimate a few years ago that hardly any debut volumes sell more than 200 copies. As a response to this ever-dwindling market-share, there seems to have been a tendency among some publishers and poets for their first books to play it rather safe and go for a pacey, jokey, zeitgeisty effect of surface phrase-making without much grit or linguistic texture and with little sense that the writing of these poems was what Ted Hughes called "a psychological necessity" for their authors. As for ideas or political resonances - well, let's not put off what few readers we have with anything too taxing or provoking.

Toby Martinez de las Rivas's excellent debut Terror resolutely baulks this trend and it's to the credit of such an established mainstream publishing-house as Faber that they've been willing to take on board a collection that's powerfully non-mainstream and challenging in its approach, difficult and dense in a way that harps back to Modernist poets like David Jones, Basil Bunting and early Geoffrey Hill but - also in the manner of a neo-Modernist - highly allusive both to earlier English poetry and history and to the literature of other countries. Despite being a formally exploratory volume which frequently calls into question what one poem calls "stability in the text" - for example, through the use of strange marginal annotations and diacritical marks - it's also an impassioned, glossolalic one, full of invocations, prayers and entreaties, and the kind of quasi-mystical struggle with religious faith and the possibility of the numinous that feels nearer to Blake, Smart or Hopkins than it does to the likes of Burnside or Symmons Roberts.

There was a further reason to be cheerful last week with the news that my publisher Penned in the Margin has been awarded £135,000 of Arts Council funding over the next three years. Perennially innovative in the projects he's tackled and with a bold intention to blur the boundaries between poetry, drama and live performance, this is a well-deserved achievement for Tom Chivers and - like the publication of Terror - a clear indication that the impetus of UK poetry doesn't reside solely in the mainstream and the populist.

PS: Falling sales-figures are affecting not just poetry but the novel too :http://www.standard.co.uk/comment/richard-godwin-dont-be-so-fast-to-write-off-the-printed-word-9594149.html

Toby Martinez de las Rivas's excellent debut Terror resolutely baulks this trend and it's to the credit of such an established mainstream publishing-house as Faber that they've been willing to take on board a collection that's powerfully non-mainstream and challenging in its approach, difficult and dense in a way that harps back to Modernist poets like David Jones, Basil Bunting and early Geoffrey Hill but - also in the manner of a neo-Modernist - highly allusive both to earlier English poetry and history and to the literature of other countries. Despite being a formally exploratory volume which frequently calls into question what one poem calls "stability in the text" - for example, through the use of strange marginal annotations and diacritical marks - it's also an impassioned, glossolalic one, full of invocations, prayers and entreaties, and the kind of quasi-mystical struggle with religious faith and the possibility of the numinous that feels nearer to Blake, Smart or Hopkins than it does to the likes of Burnside or Symmons Roberts.

There was a further reason to be cheerful last week with the news that my publisher Penned in the Margin has been awarded £135,000 of Arts Council funding over the next three years. Perennially innovative in the projects he's tackled and with a bold intention to blur the boundaries between poetry, drama and live performance, this is a well-deserved achievement for Tom Chivers and - like the publication of Terror - a clear indication that the impetus of UK poetry doesn't reside solely in the mainstream and the populist.

PS: Falling sales-figures are affecting not just poetry but the novel too :http://www.standard.co.uk/comment/richard-godwin-dont-be-so-fast-to-write-off-the-printed-word-9594149.html

Wednesday, 25 June 2014

Multiple Things Happening At Once

Review

of The Taken-Down God: Selected Poems

1997-2008 by Jorie Graham (Carcanet 2013)

If the adrenalin-fix rollercoaster of consumerism has in recent times juddered into reverse and left us dangling, our pockets upturned, where does this leave poetry, that ecumenical resource once deemed “classless and free”? With rent, energy-bills and inflated food-costs taking up most of our flatlined incomes, a £10 outlay for 60 pages with a lot of white on them seems an extravagance. The libraries and independent bookshops where one could dip into and browse new authors are becoming as rare as hen’s teeth. Publishers like Salt, faced with dwindling sales-figures, have decided to forego poetry-books altogether.

How should poets adapt to the crisis? Cut the high-brow folderol and seek a wider audience by acting as “a branch of the entertainment industry”(Hugo Williams), offering zany or epiphanic frissons to console us through this dark age? Or – as Nathan Hamilton’s recent anthology Dear World and Everyone In It implies – go the other way and locate a new hip readership among poetry-admirers bought up on the jumpy fractals of the internet but perhaps too young to remember A Various Art and the Second New York School?

If the adrenalin-fix rollercoaster of consumerism has in recent times juddered into reverse and left us dangling, our pockets upturned, where does this leave poetry, that ecumenical resource once deemed “classless and free”? With rent, energy-bills and inflated food-costs taking up most of our flatlined incomes, a £10 outlay for 60 pages with a lot of white on them seems an extravagance. The libraries and independent bookshops where one could dip into and browse new authors are becoming as rare as hen’s teeth. Publishers like Salt, faced with dwindling sales-figures, have decided to forego poetry-books altogether.

How should poets adapt to the crisis? Cut the high-brow folderol and seek a wider audience by acting as “a branch of the entertainment industry”(Hugo Williams), offering zany or epiphanic frissons to console us through this dark age? Or – as Nathan Hamilton’s recent anthology Dear World and Everyone In It implies – go the other way and locate a new hip readership among poetry-admirers bought up on the jumpy fractals of the internet but perhaps too young to remember A Various Art and the Second New York School?

If

poetry-sales are down, we are in fact undergoing something of a creative boom

in terms of the quality and range of what’s being written, and the sheer number

of able poets emerging. This ferment of poetic energy at a time of economic

downturn seems to speak of a questioning of bankrupt dominant paradigms and –

like the resurgence of interest in self-directed activities such as rural

walking – a turning away from the spurious, profit-driven hoohah of Cameronite

Britain, where the ‘grand projects’ of multicorporate enterprise give way, like

MDF stage-scenery, to reveal a gaping moral vacuum and the insidious ‘managed decline’

of public services and local communities.

Yet in the context of the international scene, the hemmed-in, self-limiting nature of much British poetry, quietist and apologetic rather than confrontational even where the approach is not mainstream, still seems apparent. If we are looking for a figure of global stature whose work embodies the determination to elaborate a more authentic discourse, a more ethically -invested voice which could help us come to grips with this bankruptcy and “make reality feel real” again, Jorie Graham would be a natural choice. One of the prime indications that we have recently entered some kind of poetic renaissance was last year’s awarding of the Forward Prize for Best Collection to her most recent book PLACE, almost the first winning volume that wasn’t a predictable safe bet by an established British mainstreamer – notably, she was only the fourth woman to have won the prize in its twenty year history and only the second American. Coming in the same year that Denise Riley, an excellent English poet who had been relegated to the avant-margins throughout her career, won Best Single Poem, Graham’s recognition seemed a momentous one.

Although The Taken-Down God doesn’t include work from PLACE, the appearance of a new Selected Poems this year can only augment the groundswell of interest fomented by the Forward win, as well as provide a necessary continuation for readers - like myself – who were enamoured of Graham’s earlier Selected, The Dream of the Unified Field (1996, Carcanet). Despite possessing a remarkably distinctive register and manner that owes little obvious to any other poet, Graham is not the kind of writer to find a mature style and stick doggedly to it; rather, the plot-curve traced by her eleven volumes is characterised by the same restless, exploratory energy as their individual poems, a concern with pushing at the boundaries and straining the limits of what the previous book had seemed to accomplish, which is frequently at the same time a straining at the limits of poetry itself and what poetry can ask of its readers. Graham makes this explicit in her Paris Review interview (http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/263/the-art-of-poetry-no-85-jorie-graham) – by the way, a source of invaluable contextual insights for anyone wanting to engage with her work – when she talks about each book being born of “the need to explore new terrain", of having not only their own thematic drifts but their own rhythmical impetus and how these two facets are intertwined.

The evolution of Graham’s poetic in Dream of the Unified Field, from the short-line stanzas and metaphysical “argument-building” of early books like Erosion through the transition to the more expansive, multi-layered syntax of Region of Unlikeness and Materialism was a gripping enough journey, although one that sometimes left the reader footsore at the roadside or temporarily waylaid in an interpretive ‘selva oscura’. The Taken-Down God charts a pathway that is at times more challenging still, progressing further in the direction of open-form, paratactic structures that seem to hover around clusters of imagery or references without ever settling into unitary narrative or formal resolution.

The difficulty we encounter in coming to terms with these poems, however, is inextricable with Graham’s long-term desire to “implicate the reader” in the whole complex process of generating meaning. Of all the contemporary poets who have assimilated literary theory into their work, consciously or otherwise, Graham (a student at the Sorbonne in 1968, as the earlier piece ‘The Hiding Place’ delineates) is perhaps the most convincing. Highly “writerly” in Barthes’ terms ( ie. demanding that the reader proactively and playfully collaborates in restoring the text to legibility) her poems work hard to problematise the dualism between text and audience, insistently hauling her or him into the scenario of the poem to confront them with the paradox of how language brings sensory-data across and attempts to motion-capture the flux of time; language that is saturated with historical and political residues: “How does one separate the acts of human will from those very acts of observation the poems undertake? There’s moral entanglement there. Is there a way of taking in the world that is not manipulative?”(ibid.)

Whereas a recurrent preoccupation of the older books was to revisit and recontextualise memory-deposits from her childhood and youth, the vividest passages in The Taken-Down God arrive when Graham manages to envelop the reader in her immediate experiences even as they unfold, “porting rather than reporting” in a startling way that somehow reconfigures the writing-process of the poem as the reading-process. Part of this is Graham’s attempt to incorporate as many levels of cognition as possible into the poem’s purview and to enact “multiple things happening at once…the punctuation involves an attempt to nest everything into the here”(ibid.)

In ‘Woods’, for example, from the volume Never, the I-narrator flicks hesitantly between wanting to evoke a sighting of a goldfinch and a reluctance to stake a claim on the bird and fix the “wind-sluiced avenued continuum” in language, the poem ultimately parodying the complacent set of tacit conventions any realist text rests upon (“Can we put our finger on it?/…I cannot, actually, dwell on this./There is no home”). This flags up a further theme within The Taken-Down God that was less evident in Dream of the Unified Field: an ecological anxiety placed in the context of man-made depredations, the poems’ harried sense of time related to Graham’s awareness that “the rate of extinction (for species) is estimated at one every nine minutes”(Footnote to Never). This concern for the endangered living world is linked to a groping towards the numinous and devotional (cf. the several pieces called ‘Praying’ in Overlord) which seems a search for a frame of reference beyond the destructive human one.

The exhilarating formal experimentation of this Selected – from the short, spaced-out single-line units of Swarm, through the rangier, prose-like rhythms and found-language in Overlord to the heavily-indented patternings of Sea-Change – manages to track audacious forages through philosophy and the history of ideas that amount to the most ambitious ongoing project into the role and scope of poetry we are privileged to have access to; yet at the same time these are vibrant, breathing poems in themselves, shot through with urgency and hard-won beauty. Against middlebrow assumptions that poetry should be a humanist salve in this difficult economic climate, Graham reminds us again and again “what poetry can, must, and will always do for us: it complicates us, it doesn’t ‘soothe’; it helps us to our paradoxical natures, it doesn’t simplify us. We do contain multitudes.”

Yet in the context of the international scene, the hemmed-in, self-limiting nature of much British poetry, quietist and apologetic rather than confrontational even where the approach is not mainstream, still seems apparent. If we are looking for a figure of global stature whose work embodies the determination to elaborate a more authentic discourse, a more ethically -invested voice which could help us come to grips with this bankruptcy and “make reality feel real” again, Jorie Graham would be a natural choice. One of the prime indications that we have recently entered some kind of poetic renaissance was last year’s awarding of the Forward Prize for Best Collection to her most recent book PLACE, almost the first winning volume that wasn’t a predictable safe bet by an established British mainstreamer – notably, she was only the fourth woman to have won the prize in its twenty year history and only the second American. Coming in the same year that Denise Riley, an excellent English poet who had been relegated to the avant-margins throughout her career, won Best Single Poem, Graham’s recognition seemed a momentous one.

Although The Taken-Down God doesn’t include work from PLACE, the appearance of a new Selected Poems this year can only augment the groundswell of interest fomented by the Forward win, as well as provide a necessary continuation for readers - like myself – who were enamoured of Graham’s earlier Selected, The Dream of the Unified Field (1996, Carcanet). Despite possessing a remarkably distinctive register and manner that owes little obvious to any other poet, Graham is not the kind of writer to find a mature style and stick doggedly to it; rather, the plot-curve traced by her eleven volumes is characterised by the same restless, exploratory energy as their individual poems, a concern with pushing at the boundaries and straining the limits of what the previous book had seemed to accomplish, which is frequently at the same time a straining at the limits of poetry itself and what poetry can ask of its readers. Graham makes this explicit in her Paris Review interview (http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/263/the-art-of-poetry-no-85-jorie-graham) – by the way, a source of invaluable contextual insights for anyone wanting to engage with her work – when she talks about each book being born of “the need to explore new terrain", of having not only their own thematic drifts but their own rhythmical impetus and how these two facets are intertwined.

The evolution of Graham’s poetic in Dream of the Unified Field, from the short-line stanzas and metaphysical “argument-building” of early books like Erosion through the transition to the more expansive, multi-layered syntax of Region of Unlikeness and Materialism was a gripping enough journey, although one that sometimes left the reader footsore at the roadside or temporarily waylaid in an interpretive ‘selva oscura’. The Taken-Down God charts a pathway that is at times more challenging still, progressing further in the direction of open-form, paratactic structures that seem to hover around clusters of imagery or references without ever settling into unitary narrative or formal resolution.

The difficulty we encounter in coming to terms with these poems, however, is inextricable with Graham’s long-term desire to “implicate the reader” in the whole complex process of generating meaning. Of all the contemporary poets who have assimilated literary theory into their work, consciously or otherwise, Graham (a student at the Sorbonne in 1968, as the earlier piece ‘The Hiding Place’ delineates) is perhaps the most convincing. Highly “writerly” in Barthes’ terms ( ie. demanding that the reader proactively and playfully collaborates in restoring the text to legibility) her poems work hard to problematise the dualism between text and audience, insistently hauling her or him into the scenario of the poem to confront them with the paradox of how language brings sensory-data across and attempts to motion-capture the flux of time; language that is saturated with historical and political residues: “How does one separate the acts of human will from those very acts of observation the poems undertake? There’s moral entanglement there. Is there a way of taking in the world that is not manipulative?”(ibid.)

Whereas a recurrent preoccupation of the older books was to revisit and recontextualise memory-deposits from her childhood and youth, the vividest passages in The Taken-Down God arrive when Graham manages to envelop the reader in her immediate experiences even as they unfold, “porting rather than reporting” in a startling way that somehow reconfigures the writing-process of the poem as the reading-process. Part of this is Graham’s attempt to incorporate as many levels of cognition as possible into the poem’s purview and to enact “multiple things happening at once…the punctuation involves an attempt to nest everything into the here”(ibid.)

In ‘Woods’, for example, from the volume Never, the I-narrator flicks hesitantly between wanting to evoke a sighting of a goldfinch and a reluctance to stake a claim on the bird and fix the “wind-sluiced avenued continuum” in language, the poem ultimately parodying the complacent set of tacit conventions any realist text rests upon (“Can we put our finger on it?/…I cannot, actually, dwell on this./There is no home”). This flags up a further theme within The Taken-Down God that was less evident in Dream of the Unified Field: an ecological anxiety placed in the context of man-made depredations, the poems’ harried sense of time related to Graham’s awareness that “the rate of extinction (for species) is estimated at one every nine minutes”(Footnote to Never). This concern for the endangered living world is linked to a groping towards the numinous and devotional (cf. the several pieces called ‘Praying’ in Overlord) which seems a search for a frame of reference beyond the destructive human one.

The exhilarating formal experimentation of this Selected – from the short, spaced-out single-line units of Swarm, through the rangier, prose-like rhythms and found-language in Overlord to the heavily-indented patternings of Sea-Change – manages to track audacious forages through philosophy and the history of ideas that amount to the most ambitious ongoing project into the role and scope of poetry we are privileged to have access to; yet at the same time these are vibrant, breathing poems in themselves, shot through with urgency and hard-won beauty. Against middlebrow assumptions that poetry should be a humanist salve in this difficult economic climate, Graham reminds us again and again “what poetry can, must, and will always do for us: it complicates us, it doesn’t ‘soothe’; it helps us to our paradoxical natures, it doesn’t simplify us. We do contain multitudes.”

(First published in Tears in the Fence, Winter 2013)

Thursday, 29 May 2014

Early Summer Round-Up

|

| Matthea Harvey |

|

| Kathryn Simmonds |

https://www.newwelshreview.com//article.php?id=760

https://www.newwelshreview.com//article.php?id=761

I also have a poem (or a sequence of four, depending on how you read it) in the new summer issue of Poetry London. I haven't seen a copy yet but there was a launch this evening (I was unable to attend) which included readings by Niall Campbell, D. Nurkse, Matthea Harvey and Angie Estes, all intriguing poets so should be a strong edition.

Afterword: I have it now and it's definitely worth a look. Poems by Denise Riley, Colette Bryce and Eoghan Walls, reviews of books by Christopher Middleton, Gottfried Benn (translated by Michael Hofmann) and Derek Mahon.

Thursday, 22 May 2014

Monday, 12 May 2014

JHW 1942-2014

And now John has died. I realise I reflect too often in this blog on the passing of poets - no doubt a sign of aging - but there always seems to me something especially tragic when a poet leaves the world. What was it Pasternak called them? "Hostages of eternity in the hands of time". Something of this although there is something assuring about that quote too; perhaps something also like this line from a Lorrie Moore story: "What is beautiful is seized".

And now John has died. I realise I reflect too often in this blog on the passing of poets - no doubt a sign of aging - but there always seems to me something especially tragic when a poet leaves the world. What was it Pasternak called them? "Hostages of eternity in the hands of time". Something of this although there is something assuring about that quote too; perhaps something also like this line from a Lorrie Moore story: "What is beautiful is seized".

But John was a friend. He would have laughed at me for bandying such grandiose quotations. Like most genuine poets he didn't have much time for the pretentious baloney that's spouted about poetry and literature; he preferred to get on with it and let his work do the talking. I can only echo the generous tribute written by Todd Swift on Eyewear the other day about both John the man and John the poet, although I knew him for a much shorter time than Todd.

I missed John when he made his final trip to England three weeks ago to read from his new volume The Golden Age of Smoking at the LRB Bookshop and I had been meaning to email him to see how it had gone ever since I've been back in London. On the other hand I'm really glad I had the opportunity to conduct an interview with John last autumn on this blog and I hope now it reads as a last summing-up of his views on poetry and a potted autobiography for those wishing to look back. What comes through, however, is the sense of himself as a figure somewhat eclipsed by the poetry scene he had not so long ago been a distinctive part of, a disillusion born of struggling to get quirky, unconventional poems like his heard above the chugging drone of mediocrity. I hope that John's death will occasion some form of revaluation of his achievement (perhaps a Collected, for example, will appear before long) and see his reputation restored to its proper standing.

I just flicked through my favourite book of his, Canada, for a line or stanza appropriate for this moment but I could find nothing mournful or gloomy in the whole collection. In fact almost every poem is full of energy, good humour and zing: he was very much a poet "on the side of life" and as a person too. All the sadder, then, that he is now gone.

Obituary by his friend John Lucas here.

Sunday, 4 May 2014

Rosemary Tonks 1928-2014

I wonder if a secondary motive for not seeing a career in poetry as a viable option for either Tonks or Mirrlees (or equally Laura Riding, another apostate) was the anomalous nature of being a female Modernist poet who didn't wish to conform to the inherited stereotypes foisted upon them by the literary establishment. Tonks was clearly never going to be a mainstream poet and what few notices I've found about her (written by men) do often focus somewhat belittlingly on the frisky, sensuous loucheness of her work, which is one of its great appeals and makes it so redolent of its time: how many male poets of the '60s capture the flavour of the period so well? (The Liverpool poets, for example, seem juvenile in comparison.)

For a taster of her brilliantly-titled volume Iliad of Broken Sentences try this discontinued blog.

Guardian obituary here.

Wednesday, 30 April 2014

Florence, Siena, Dante

I spent a week in Florence and Siena over the Easter break, a welcome transfusion of sunlight, culture and architectural splendour. Among other fascinating explorations we chanced upon the Casa di Dante in a backstreet near the Duomo, just after enjoying the most wonderful lunch of ribollita and chianti in a tiny, narrow trattoria round the corner.

The Dante museum was less than illuminating but Florence, so well preserved despite the incursion of designer stores, MacDonalds and multinational crowds - and even more so the mediaeval labyrinth of Siena - felt like the perfect spur to inspire me to revisit the Divina Commedia and immerse myself not only in what CH Sisson calls the "luminous clarity" of Dante's early Italian (and me only a Duolingo novice, hoping the poem will "communicate before it is understood") but also in the complex historical contexts of this densely-wrought masterpiece, poetic cross-currents and echoes which seemed to resonate around me as I walked.

"But the first sight of Dante, for one who catches a glimpse from afar, is of a tailor narrowing his eyes to thread a needle, or a gaggle of cranes stretched across the sky. That does not give you a style to imitate; it gives you a perception of the maximum which can be done, in a few words, to evoke a physical presence." (Sisson again, 'On Translating Dante')

Wednesday, 26 March 2014

The The - This is The Day

I was reminded of this when it appeared on an episode of Fresh Meat recently. As much as the first Smiths album, Prefab Sprout's Swoon and Postcard-era Orange Juice, Soul Mining by The The was part of my teenage vinyl-pantheon, laconic anthems for bedroomed youth that seemed to vindicate and feed my sociophobic introspection.

And as with Morrissey, McAloon and Collins, it was the lyrics that seized my interest as much as the music. Where Matt Johnson diverged from the wittier, more tongue-in-cheek tristesses of the others - and in this allying him to another of my favourite lyricists, Ian Curtis of Joy Division - was in an approach seemingly grounded in the gloomy, no doubt self-obsessive existentialism I had begun to explore in my early reading. I remember the thrill of connectivity I felt when I came across a line from another single from Soul Mining, 'Perfect Day', in Sartre's Nausea: "What is there to fear from such a regular world?" Johnson's lines had the feel of diary-jottings from a soul in crisis: what a brilliant opening couplet "You didn't wake up this morning cos you didn't go to bed/You were watching the whites of your eyes turn red" is. The incongruity of pairing such angst with catchy, jaunty melodies played on instruments like accordion, harmonica and acoustic guitar was no doubt the secret of Soul Mining's unique - and continuing - appeal.

(Unlike Jean-Paul Sartre and existentialism, whose appeal didn't last beyond those teenage, bedroomed years.)

Monday, 17 March 2014

The Idea of Creativity

"It is creative apperception more than anything else that makes the individual feel that life is worth living. Contrasted with this is a relationship to external reality which is one of compliance, the world and its details being recognised but only as something to be fitted in with or demanding adaptation. Compliance carries with it a sense of futility for the individual and is associated with the idea that nothing matters and that life is not worth living. In a tantalizing way many individuals have experienced just enough of creative living to recognise that for most of their time they are living uncreatively, as if caught up in the creativity of someone else, or of a machine..."

"It is assumed here that the task of reality-acceptance is never completed, that no human being is free from the strain of relating inner and outer reality, and that relief from this strain is provided by an intermediate area of experience which is not challenged (arts, religion etc.) This intermediate area is in direct continuity with the play area of the small child who is 'lost' in play."

DW Winnicott, Playing and Reality (1971)

"It is assumed here that the task of reality-acceptance is never completed, that no human being is free from the strain of relating inner and outer reality, and that relief from this strain is provided by an intermediate area of experience which is not challenged (arts, religion etc.) This intermediate area is in direct continuity with the play area of the small child who is 'lost' in play."

DW Winnicott, Playing and Reality (1971)

Saturday, 8 March 2014

Sebastian Barker 1945 - 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)